- Home

- Rosanne Dingli

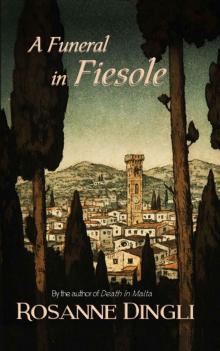

A Funeral in Fiesole Page 14

A Funeral in Fiesole Read online

Page 14

‘Listen, carino, listen. Go and search up in the roof of the back house. You know very well – the back house where Donato and I used to live? Go to the little house, and up in the roof space, in the … what do you call it?’

‘The attic?’

‘Ecco – il sottotetto. Yes, yes – up in the attic you will find something your beautiful mother wanted you to have, only you. Don’t tell anyone else, capito?’

I understood. ‘But what is it, Matilde?’

She smiled in a mysterious way. ‘It will be very clear when you find it. Buona fortuna, caro.’

She wished me good fortune, in exactly the same way as she would when we all went back to school in the autumn, when we were kids. I could see she was tired. I kissed her on both cheeks and Grant and I made our farewells and walked back to the car.

‘Such a sweet little grannie, she is.’

‘Oh Grant – she used to have such energy. She practically ran the villa … chasing us, cooking, cleaning, ironing, and keeping Mama company in the garden from time to time. It couldn’t have been easy, with us four kids making such a noise and such a mess.’

‘And talking, talking, talking!’

I twisted sideways. ‘Do we talk a lot?’

Grant laughed. ‘Do you talk! And you all have the same habit of saying something three times, in three different … distinct … varied … ways!’ He held up three fingers as he said the words.

‘Mama’s speech patterns were … well, repetitive. Are mine?’

‘You all do it.’

‘Matilde became used to us and our mess and noise … and repetition … I suppose.’

‘She treasured every minute, if her eyes reflected anything.’

‘I guess so. What do you think is in the attic at the small back house, up at the villa, then?’

‘What attic? You’ve got to tell me what went on. I couldn’t understand a word, the way you gabbled on and on!’

I laughed and explained what Matilde had said about something hidden in the attic, as we drove all the way back to Fiesole.

‘Do you think she actually meant I should keep it a secret?’

‘If it’s a bag of gold coins you feasibly could, but if it’s anything bigger you’d have to explain to the other three.’

‘Hm. I’ll have a peep before we all leave tomorrow.’

‘I’m looking forward to coming back, Brod.’

‘Ha ha, Grant. We’ll have to make real decisions about all that at some point. We must still have the big final deciding discussion.’

I gazed out of the car window and wondered what we would end up doing, about the villa, about the inheritance, about the way it had all gone. I didn’t know whether to be grateful to Mama for how she had divided it all up; or to be sorry I stirred such an argument up the night before, and infuriated Suzanna. I also seemed to have scared Nigel. Poor Nigel – I didn’t mean to jolt him. It’s gone absolutely the right way for him.

There was still the question of Paola. Although a bit less wound up than the day we all arrived, and a bit less nervous than on the day of the funeral, my older sister seemed sometimes edgy and sometimes composed; exerting enormous control over her emotions and every word she let out of her mouth. Surely she wasn’t always so? I should get her alone and have a nice long chat. I had nearly forgotten her long marriage had only recently broken down and I still hadn’t said a word to her about it all.

I might corner her in the hall, in front of the wall gods, in front of her Neptune, and my Diana and her fading hounds, quite as I used to do as a boy, and sweeten her up with something like roller skates or a box of books or … I wonder how she would react if I mentioned a pallet of young plants?

Paola

Observation

What better place to address a family than at a dinner table in a neutral place, such as a restaurant? We dithered a bit when taking our places, and although I felt I should sit next to Brod, found Grant was somehow inserted between us, with Lori and a reluctant Tad sitting directly across from us.

We all craned our necks up to the bikes swinging above us, in the updrafts of breath, laughter, and the aromas of food from plated dinners coming out of the kitchen.

‘Let’s talk about the dichiarazione di successione.’ It was obviously easier to use those words than the English equivalent.

They all stopped talking and looked at me. Did I seem ready to them, to discuss what had been on all our minds since we sat in Mama’s sitting room in front of the pompous notary, Dottor Umberto Ugobaldi, in his steel-rimmed specs?

No one disagreed, but there was not a word from our table for a long interlude, and chatter came in from others. The clink-chink-dingle of crockery, cutlery, and glassware was all about us.

‘Before we do,’ Suzanna said, raising her head and glass and demanding attention, ‘I should say I’m going to see Matilde tomorrow. Lewis and I ought to be on our way very soon. That boat won’t wait for us forever. We can make an offer right now. A good one.’

‘Oh? So you’re not buying it new?’

I sighed at Brod’s question and glared at him. Did he not know some boats were special, and that our sister could talk forever about it? It would stretch Suzanna’s side-bar and take more time than I had patience for. I wanted to talk about Mama’s bequest and how – or whether – it would affect the ways we were starting to think about things. Was everyone willing to sign the acceptance document? I wanted to know, and was pretty certain we all did. If everyone was leaving soon, we’d have to sign quickly.

My sister smiled. ‘Lewis and I have found the ideal sailing boat – it has a history. It’s the very same vessel Alex de Cassius took around the world!’ A bit dismayed at the blank faces, she went on. ‘Alex de Cassius took Char-à-banc around the world last year, after his umpteenth Sydney-Hobart race, in which he’s never come in later than tenth! Surely … oh, all right, you don’t know!’ She laughed and looked around at us all once more.

‘So it’s a famous boat, Suzanna?’ I had to say something to hurry the topic along.

‘Yes, very famous, and we are texting and emailing away, right now, with Alex, to tell him we’re very interested.’

‘What kind is it?’ Brod in all probability knew less than I did about boats. Perhaps he was truly curious.

Suzanna’s eyes brightened, as Harriet’s glazed over. My sister smiled. ‘A Kaufman Forty-Seven, a cutter, it is. Lots of room, and we can have crew – two, or three, put up in the aft cabin.’

‘Crew!’

Lori’s eyes widened. ‘Wow – three Popeyes in blue and white.’

We all laughed.

‘So how big …’

‘Nearly sixteen metres … in length.’

I was surprised at its size. It sounded like a very expensive craft. ‘Where’s the boat right now?’

‘Malta. Char-à-banc is in Malta, which is quite convenient, you’ll agree, so I’ll hop on a plane as soon as possible, Lewis will take Otto home to be cared for, won’t you, darling? And by the end of the month she’ll be on a hard stand being de-fouled, re-rigged and all, ready for us to take her to … ‘ She counted off on long fingers. ‘… Piraeus, Venice, Portofino, Lisbon, Istanbul, Villefranche-sur-Mer, … and much later on to Cowes. It’s so exciting.’ She shook her head at the immobile little pet whose snout rested on her forearm. The dog had hardly moved since their arrival in Fiesole. I doubt I had heard the tiniest yelp, whine, or growl.

‘Will the dog … um, will Otto go with you on the boat at some stage?’

Her eyes widened. ‘Of course. Eventually – he needs his proper shots and things soon. There’s forty-seven feet of boat. Plenty of room for Otto!’

‘All settled and decided, you sound, Suzanna.’ Nigel sat at the end with Harriet on his right. They both nodded in the same way.

‘Very nearly settled. There’s one other very interested party, but we should be able to put in a solid decent bid now. Char-à-banc is very nearly ours!’

‘It’

s an unusual name for a boat.’ I might as well carry on with the conversation. There would be time enough to discuss the will. I was starting to doubt whether we would ever hear each other’s opinions on signing the document. I poured more wine and sat back, prepared to listen to Suzanna.

Unusually for him, Lewis replied, after carefully placing his fork on an empty plate. ‘It’s a French word meaning a carriage with wooden benches. Or an early type of open bus. Amusing. Amusing name for a boat, but it’s obvious why it was given such a name.’

I could hear Brod hum from where I sat. ‘No, it isn’t, Lewis. Why’s it obvious?’

‘Well, Brod – the de Cassius family had one of the most famous bus companies in France and Italy … you know, along the Riviera, for decades. Nearly a hundred years. There’s still a trucking company called de Cassius somewhere.’

‘In Belgium. They have a picture of our boat on the office wall!’ Suzanna seemed very confident they would bring off the purchase.

‘The very same one!’

‘Yes, we’ve seen it on the internet. So we’re very keen, aren’t we, Lewis?’

Lewis seemed like he had to work on keen, but was not far from happy. Making Suzanna happy was what he was all about.

‘Well.’ Now I could divert them all to talk about the will. No, not yet. Someone ordered more wine, and we were all talking about desserts and coffees. ‘Well – so Mama’s foresight has set you up fantastically well, Suzanna.’

What could she do but nod and smile? ‘Yes, of course. I didn’t know it was what she was going to do. I thought she would leave a … you know, what people would term a normal will, in which everything was lumped together and split four ways.’

Nigel lifted his coffee cup. ‘Mama was not people. There was nothing normal about her. Well, you know what I mean.’

Harriet, who sat so close to her husband their shoulders touched, glanced up from her plate of artfully arranged ice cream. ‘She wasn’t weird, though. She was extraordinary enough to be unusual … but she wasn’t weird.’

I shot her a half scowl which I had no doubt would be seen as disapproving by everyone there. It had reached a point where everyone knew – definitely, after all these years – that Harriet and I would never get on. She tolerated my presence when it was necessary, and no more. Too late, I softened my gaze, when she had looked away.

Despite Harriet’s very annoying remark, it developed swiftly into a reminiscent discussion about Mama. Quite comforting. Despite confusing and conflicting memories, we all remembered her well.

I planned to forget about the will and enjoy it. The temptation to startle them with memories I thought were unique to my mind had softened a bit, and I resisted the urge to remind them about the time she tried to tackle a fallen tree with a little hacksaw, or how she dealt with one enormous failed canvas, a very big portrait of us all together, which she had stuck into a bonfire between the lawn on the lower terrace and the rubble wall. She had tried to paint us in a group, one summer, and with one thing and another, it became an oddly-planned portrait in colours she thought were ‘wrong, all wrong’. She hacked at it in frustration, and we all ended up toasting bits of bread on long sticks around its flames.

‘She taught us quite a lot,’ Brod said, mostly to Grant.

‘She even taught us to do things she couldn’t do. Like roller skate.’

I thought about it. ‘Oh – true. I never saw her skate. I never saw her dive off the springboard down at the Florence pool, either. But I seem to remember she showed me how.’

‘Indeed! Mama taught us how!’

‘And she never signed notes or letters with Mama.’

‘She got the habit from Papa.’ Suzanna leaned forward. ‘I still have a birthday card he sent when Brod and I were very little. I think it was my first year at boarding school. It’s signed Roland.’

‘I got one too.’

‘I must have a couple.’

‘We all had letters from Mama, two a term. She never missed one.’

‘All signed Nina.’

I risked taking the prompt. ‘She signed the will Nina.’

‘Paola – this is neither the time, nor the place.’ Nigel seemed annoyed.

My gasp reached his ears across the space separating us. ‘You didn’t want to talk about the will at home, either.’

‘Oh, I don’t know about you, Paola – but it no longer feels like home to me.’ Suzanna made a face.

‘Suzanna … don’t.’ Even Brod saw how critical her remarks could be.

‘No – true. It’s either because there are so many of us staying, this time … ’

‘We’re not staying there.’ Brod was quick to put her right.

‘ … or because it’s fallen into disrepair.’

‘It’s not so bad.’

‘Yes, it is, Nigel, starting with the frescoes in the hall. I don’t know why you didn’t have them painted over when you and Harriet were caring for Mama. I don’t know how you could stand to pass them in and out of the hall … up and down the stairs … back and forth to the …’

Nigel cut Suzanna off. ‘We couldn’t make such decisions when Mama was still alive!’

Brod leaned toward Grant. ‘Grant loves those frescoes.’

His partner gave a slight nod, but I could see his reluctance to enter an animated debate with Suzanna. ‘Um - they’re quite fabulous, and should be restored. The whole house …’ He paused, and I saw why. Grant did not feel he ought to make any sort of comment, and left it for Brod and his family to discuss. He caught my eye, and I saw a glint of something there. So tactful, so understanding. He was a sensitive man. The world would be an amazing place if more men were like Grant.

‘It unquestionably feels like home to me. I mean – we haven’t even slept in it, and it feels like home. We should have one night there, eh, Grant?’ Brod folded his napkin, finished his coffee, and smiled his broad smile. ‘Hm – tomorrow night? Before we drive to the airport?’

‘You should.’ There was Harriet, using her proprietary tone again. Even after understanding the contents of Mama’s will, she still acted like the villa was hers.

I edged forward. ‘Yes, Brod, you should.’ I addressed his partner. ‘You should get a feel for what it’s like to wake there, Grant. The morning light. The morning lull, and then the afternoon breeze.’

Harriet seemed a bit stung and withdrew. She grimaced comically at Nigel, who smiled back at her. It’s all right, he seemed to signal, with a similarly, comically, stretched mouth.

One thing was certain in my mind. Mama knew Harriet and I would never agree on anything, so she had left a carefully thought-out will for a reason. That reason.

Everyone stopped talking when Tad uttered a long clear sentence none of us expected. He was thin, pale, and bit his nails down to the quick, but his voice was surprisingly mature, with a startling tenor register, coming across from me, where he was in the process of demolishing an enormous dessert.

My nephew sounded very adult. ‘Gramma’s will is a very clever piece of writing. It was as if she was there, telling everyone what the best solution was to everything. Not simply money and houses and necklaces and who should have what. But, you know, about life and love and how everyone ought to go about enjoying stuff.’

His mother gave him a strange glance. His father’s jaw dropped. I smiled, rather glad to have someone else declare what we all should have realized earlier. Not even recalling whether he was in the room for the reading, I saw it as a moving statement. I thought his mother might take an example from the way he spoke; rarely, but with infinite meaning.

Lori looked sideways at her brother, amazed he had uttered so many words at once. ‘What – like you enjoy your blazer, Tad?’

He regarded his half-finished crème brûlée.

‘Brod – stay in Basile’s room.’ I felt they would like that room best, since Brod’s old bedroom was so small.

‘Basile’s room?’ Many voices rose at once.

What did

I hear in the various tones rising and falling around the table? It was so obvious I was the only one to give any thought to how significant the artist’s presence was in all our lives. How easily they forgot. ‘Yes – it was Basile’s room, for about four summers. He kept his painting gear in the next room. It’s the bedroom with rust-coloured walls and the curly cornices. Does no one remember? I remember him painting in there when it was windy. There were canvases stacked along the walls. I remember his bedroom door was always closed.’

‘What else?’ Grant was always interested when I mentioned art and architectural details. ‘I think I’ve seen the room. The cornices are art nouveau … sort of.’

‘It was one of the rooms Papa renovated, years back. Donato found the taps in the bathroom from some salvage place in Prato.’

‘The stuff you remember, Paola.’

‘She brings back things I’d never have thought of otherwise.’

‘Why do you think you remember so much, Auntie Paola?’

I spoke to Lori. ‘I tended to be quiet. I observed a lot.’ I laughed. ‘A typical oldest-child habit, I guess.’

‘One thing I certainly wasn’t … observant. Or quiet!’ Suzanna spoke to Lewis, but we all heard, and laughed. You had to give it to Suzanna; she knew herself, and could be unapologetic and funny with it, no matter how acerbically she phrased her words.

Lively conversation started around the table, and the two brothers walked off together to settle the bill. I let them. My head and heart were taken by memories of Basile, who would take and guide my hand with the brush, to trace outlines of some landscape. ‘Distance … remember distance. It’s as important between a tree, a hill, and a church as it is between the nose, the lips, and the chin. Distance. Always. Accurate distance means accurate likeness.’

I never painted seriously, and I wondered whether his advice had anything to do with the way I wrote – with my writing style, in which I placed distance between characters, between events, between the premises on which I constructed my stories. Distance between me and my readers? Perhaps there was a bit of Basile in what I did and how I wrote.

A Funeral in Fiesole

A Funeral in Fiesole